During the 1980s, Eberswalder Wurstwerke of the then German Democratic Republic was the largest sausage producer in Europe, with approximately 3,000 employees. The 65 hectare production site had its own hair salon, medical clinic, library, and restaurant. Those communist days have passed irreversibly. Last week, the approximately 500 remaining employees learned that the relatively new West German owner of the company, which enjoys the devotion of loyal customers for its bratwurst and Schorfheider Knüppelsalami, would close the factory in Britz by the end of February.

Economic stagnation and closures

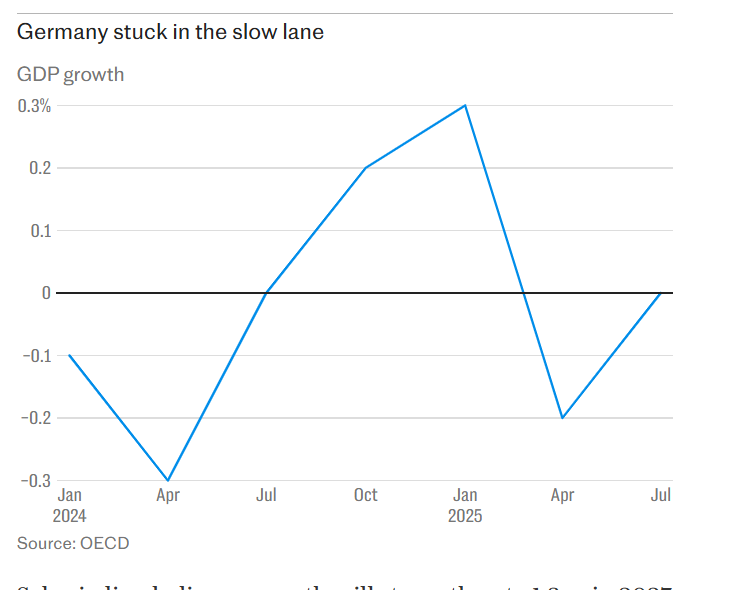

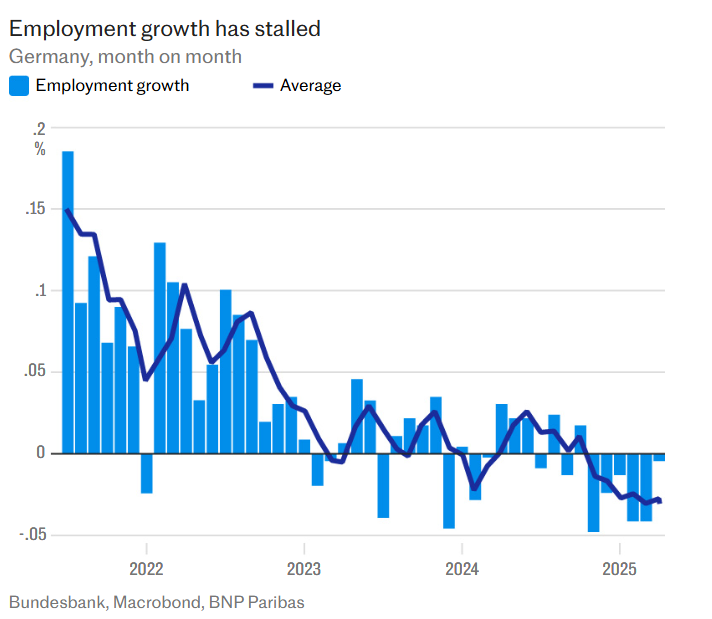

Germany’s economy, the third largest in the world by nominal GDP, has remained stagnant for three years, and factory closures and bankruptcies are reaching alarming levels. On January 8, Zalando, a major German online fashion retailer, announced that it would close a logistics center employing 2,700 workers in Erfurt, also in eastern Germany. Preliminary data from Destatis, the German statistical office, show that bankruptcies in December increased by 15% compared with the same month of 2024. The transport, hospitality, and construction sectors were hit particularly hard. The annual total of more than 17,600 company bankruptcies last year was the highest in 20 years, according to the Leibniz Institute for Economic Research. Most discouraging for Germans was the wave of well known companies that collapsed. Last year these included some of the biggest names in the country: Goertz (shoes), Gerry Weber and Esprit (fashion), Groschenmarkt (retail), Karrie Bau (construction), and Zoo Zajac (the largest pet supplies chain in the world). German industry once functioned as an anchor of stability, smoothing fluctuations in other sectors. No longer. Export oriented industries are particularly vulnerable to global conflicts, tariffs, and high energy prices. The entire economic model of the country does not fit the new realities. Until it adapts, even sausage producers will find themselves “on the chopping block”.

The catalyst of the war in Ukraine

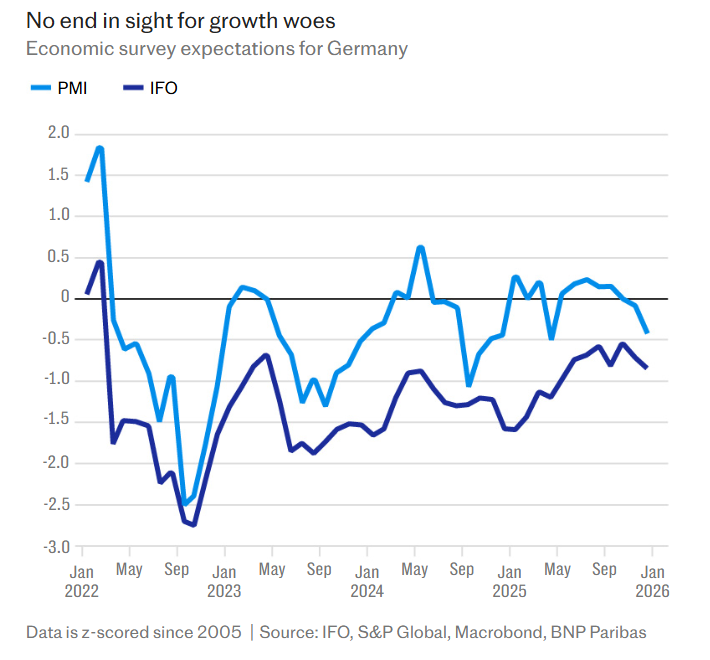

Four years after the start of the war in Ukraine, the country has partly managed to free itself from Russian oil and natural gas, but with unemployment now approaching three million and with major losses in key industries such as the automotive sector, as the trade war of Donald Trump causes chaos in manufacturing, the largest economy in Europe is now facing an identity crisis. Friedrich Merz, Chancellor of Germany, described the short term challenges in a letter to his coalition partners in the Bundestag last week. He warned that for large parts of industry it is “a matter of life or death”. “The situation of German industry is very critical at certain points,” he warned. “Industrial giants as well as a significant number of medium sized and small enterprises are facing major challenges, in many companies jobs are being lost.” But Merz warned last week that the increase in the country’s productivity “is no longer good enough”. He criticized the “changed global economic conditions” as well as high labor costs and bureaucracy for delaying growth. Recent data indicate that this weakness will continue in the near future. Despite Berlin’s much publicized spending on defense and infrastructure, the country’s central bank cut its growth forecast for 2026 to just 0.6%. Ifo, a think tank, predicts similarly weak growth of just 0.8%. Others are more optimistic, with indications that the 500 billion euro stimulus package is beginning to bear fruit. Holger Schmieding, chief economist of Berenberg Bank, notes that domestic orders are beginning to rise, even though exports remain weak. Berenberg also expects the economy to expand by only 0.7% this year, with government spending accounting for more than half of this growth. Schmieding believes that growth will strengthen to 1.3% in 2027 as the stimulus package reaches “full force” and consumers and businesses begin to spend more. However, he adds that Germany’s decision to change its constitution to allow unlimited debt financing for defense spending above 1% of GDP will not be the growth catalyst that some claim it to be. “Some companies will struggle to fulfill all the new orders for tanks and drones and to upgrade as many railway lines as possible with their growing order backlog,” he said.

Adapting to the new realities

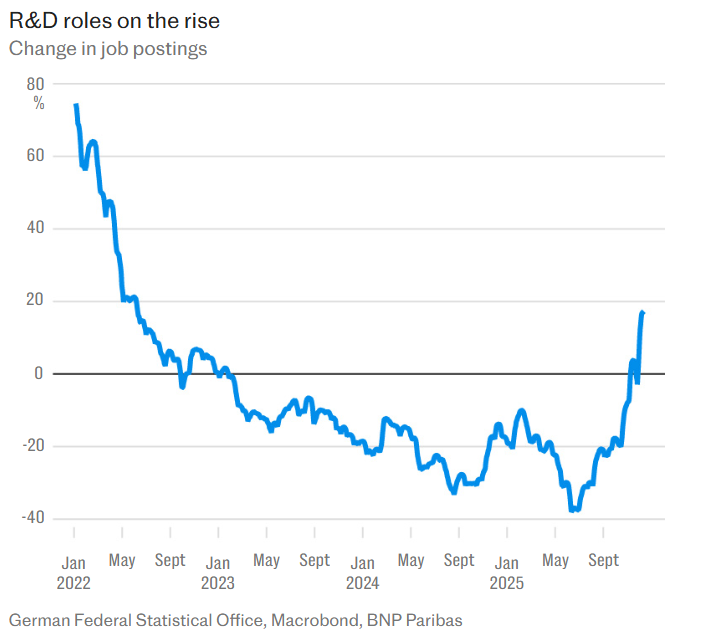

Economist Peter Bofinger, who served as one of Germany’s so called “wise men” on the Council of Economic Experts, worries that politicians will focus too much on subsidizing old industries instead of supporting new ones. “The problem is that we do not have a vibrant digital sector,” he says. “We also do not have a very strong financial services sector like the United Kingdom, so a large part of our prosperity depends on industry, and of course this is now under attack from China, which can produce the same things we produce but more cheaply.” His concern is that lawmakers will focus excessively on energy subsidies at the expense of innovation. “Innovation is a bright spot in the somewhat gray and foggy picture of the German economy,” he says, with official data indicating that jobs related to research and development are increasing. Bofinger says that Germany has a golden opportunity as it more than doubles its military spending to reach the NATO spending target of 3.5% of GDP. “In my view, the ace up the sleeve is the defense industry, which historically supported all kinds of technological innovation,” he says. This is the same advice offered by Paolo Surico of London Business School, whose work has influenced policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic. Surico argues that some of the best innovations and inventions came from investments in defense, including GPS and even the internet. He cites the example of penicillin, which was discovered accidentally by Scottish scientist Sir Alexander Fleming in 1928. It was developed only more than a decade later when Vannevar Bush, then an adviser to Franklin Roosevelt, the United States president during World War II, asked companies to scale up production of the drug for use by the American military. Pfizer, then a chemical company, rose to the challenge and used the technology to produce enough penicillin so that every allied soldier had a dose of the antibiotic on D Day.

A pharmaceutical giant was born, and a company that later developed the Covid vaccine. Surico argues that government investment in research and development, as well as in weapons and soldiers, would be a better use of public resources and an investment in the future. For this reason, he suggests that repeating old defense tactics, such as Ronald Reagan’s strategy of a 600 ship navy in the 1980s, is likely to be less effective in a world where brain power can generate more economic benefit than firepower. “You can create two kinds of deterrence,” Surico says. “The Reagan deterrence that builds ships, or the John F Kennedy deterrence, the space race, that gets to the Moon first. My view is that Kennedy’s deterrence creates far more prosperity than Reagan’s.” Bofinger hopes that Germany can stop clinging to its past. “What we have now are traditional classic Keynesian demand support policies with more spending on infrastructure and some tax cuts, which is why most people believe that this year we will have about 1% growth to get out of this stagnation,” he says. However, he warns that the optimism will not last. “The biggest threat to the German economy is that the government will pour too much money into trying to support old industries that will die sooner or later.” Bofinger says that Germans should take a page from the book of Joseph Schumpeter. The economist coined the term “creative destruction” in the 1940s to emphasize that innovation causes the death of established businesses because it also creates new opportunities. “For the moment, we have too much Keynes and not enough Schumpeter,” he says. “Of course, innovation does not come out of nowhere, it really needs funding, and that is the way Germany can grow its economy.”

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών