With Bulgaria's eight prime ministers and chaotic corruption, the euro enters the final stretch to the cliff.

On January 1, Bulgaria became the 21st member of the eurozone. However, the setting could not be worse. The country is plunged into political turmoil, corruption is widespread, and its debts are mounting. In reality, the next crisis for Europe is looming on the horizon – and ironically, Brussels is welcoming it with open arms.

This is not exactly the smooth transition that officials at the European Central Bank would have hoped for. As the Bulgarian lev joins the lira, peseta, and franc in the history books, one would hope the zone would welcome a new member with a stable government, enthusiastic public support, and a thriving industrial base. Instead, its government has just collapsed, there are protests over corruption, and ordinary Bulgarians—who were inevitably never asked via a referendum—seem to view the entire project with great hostility. Nevertheless, the country will be pushed into a monetary union with Germany and France regardless.

What could go wrong?

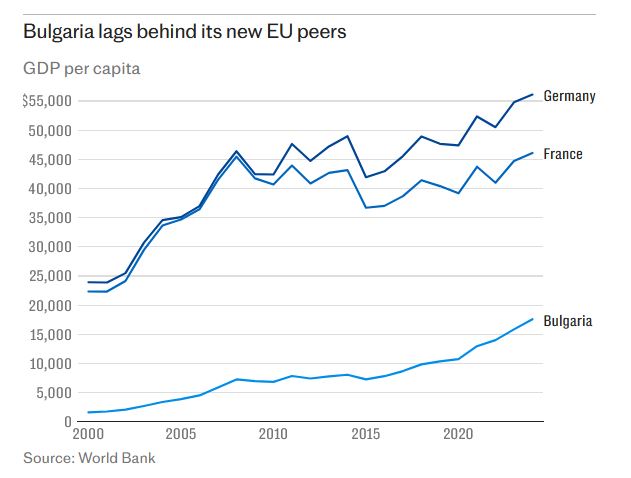

After all, what could go wrong? Well, quite a few things, as it turns out. Without any intention of disparaging Bulgaria, the country is not a model of fiscal responsibility or political stability. Bulgaria ranks among the poorest EU countries, with a GDP per capita of $17,600 (£13,090), according to World Bank data, compared to $56,000 in Germany and $46,000 in France in 2024. It is far, very far, from its new partners.

It has repeatedly failed regarding its inflation target, with the rate reaching 16% as recently as 2022. It is deeply politically divided, with a disorienting succession of elections and eight prime ministers since 2020, including caretaker governments. And it does not possess a particularly good track record in repaying its debts. The years it was part of the Soviet bloc don't really count, but before that, it had defaulted in 1915 and 1932. To be fair, it is not in the same category as Greece, which has defaulted six times in the last 200 years; however, its history is anything but impressive. Similarly, the lev has undergone four major revaluations since Bulgaria became an independent state. A good place to store a lifetime's savings? Probably not. By almost any criteria one chooses, it would be difficult to find a worse candidate for a monetary union with Germany or the Netherlands. Of course, on one level, the fact that more countries are joining the single currency is a sign of strength. However, it is worth noting that truly successful economies within the EU, such as Poland and the Czech Republic, show absolutely no interest in having anything to do with it, despite being legally obligated to join.

What may follow

Against all this, it is not hard to see what may follow. A succession of unstable governments will increase spending to stay in power. Money will be channeled to cronies, and borrowing—now implicitly supported by the European Central Bank (ECB)—will constantly swell until the scheme becomes unsustainable, markets pull the plug, and the economy collapses. In short, it will be the Greek crisis all over again.

The problem is that the Eurozone is in a much worse state than when the last crisis broke out in 2010. France's debts have spiraled out of control: the debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 81% to 114%. Germany has embarked on a massive, debt-financed spending spree and is no longer in a position to bail out its neighbors. The EU itself has now taken on enormous debts. We do not have a clear picture of what the ECB's balance sheet looks like after years of covert market interventions. However, it is not at all encouraging that last year it announced record losses of nearly €8 billion (£7 billion), or that it now possesses negative equity, or that the Governor of the Banque de France, François Villeroy de Galhau, felt the need to point out in October that the central bank is not bankrupt (thanks, Francois — that’s reassuring, if only in the sense of "the board has full confidence in the manager").

It is possible that a strong and successful Eurozone could absorb a problematic Bulgaria. But this one? This amounts to an invitation for trouble. Even more paradoxical is the fact that Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer is determined to tie the UK more closely to the EU at the worst possible moment. Why would Great Britain, with its own massive debts, want to be potentially exposed to politicians in Sofia who spend lavishly or risk crisis contagion from a chaotic Eurozone to its own already fragile bond markets?

When Greece joined the Eurozone 25 years ago, the bloc was still relatively strong, with much lower total debt, fiscal rules that countries paid at least some attention to, and output roughly equal to that of the US. Discussions about whether the euro would replace the dollar as the global reserve currency had some credibility. Today, the bloc is drowning in debt. It has abandoned all restraint on borrowing, its industrial base is collapsing, it depends on imported energy, and it has fallen far behind the US. Soon it will be behind China too. One spark is enough to trigger a new Greece-style crisis. Bulgaria might be preparing to provide it and, from here on, it is already too late to do anything to prevent it.

Risk or cool-headed transition for Bulgaria?

Bulgaria has so far followed a conservative fiscal policy, with debt below 30% of GDP – well below the 60% limit allowed by the eurozone. By joining the euro, the "debt brake" of the currency board will be abolished, giving Sofia the ability to seek financing from international markets as a reliable member of the zone. This, however, also brings temptation: if politicians decide to follow Greek paths, the country could find itself facing its own "Greek scenario."

The eurozone, however, monitors every country closely, and the massive manipulations that led Greece to crisis will no longer be possible. The message is clear: Bulgaria has all the tools for a safe transition at its disposal, but its fate will depend on the decisions of Bulgarian politicians and the vigilance of citizens through elections. Greece's history shows how quickly the euphoria of joining the euro can turn into a nightmare for a country that does not maintain discipline in public finances. Bulgaria now stands before the mirror of history – and the next page could be either success or terror.

Why the Eurozone hides nightmares

The Euro... it sounds stable, safe, almost invulnerable. However, the "buts" are many. In this case, it is useful to refer to the term "Optimal Currency Area" (OCA) (pioneered by Robert Mundell), defined as a geographical area where economic efficiency is maximized by having a single currency. The basic criteria defining an OCA are:

-

Wage and price flexibility: If wages and prices can adjust quickly to economic shocks, countries can deal with crises without needing their own currency.

-

Labor mobility: Workers must be able to move easily from a country in recession to a country that is growing.

-

Integrated financial systems and capital transfers: The existence of strong support and financing mechanisms can replace the loss of national monetary policy.

-

Convergence of economic cycles: Participating countries must have relatively synchronized economic fluctuations.

-

Fiscal transfers: Common mechanisms that allow the transfer of resources from rich to poorer regions to mitigate inequalities.

However, in the Eurozone:

-

Labor mobility is limited. Languages, culture, and administrative barriers make mass movement of workers difficult.

-

There are large differences regarding economic cycles. Countries like Greece and Portugal often have different economic cycles than Germany or the Netherlands.

-

Eurozone countries cannot use currency devaluation to improve their competitiveness. Wage flexibility is limited in many countries, especially in the public sector.

-

The Eurozone has limited means of transferring resources from rich to poorer countries. The Stability Pact limits state deficits and provides limited intervention capability.

-

Integrated financial systems do not exist. There is the ECB and mechanisms like the ESM, but they do not fully cover the loss of national monetary policy.

Consequently, the Eurozone does not fully meet the criteria of an optimal currency area. There are significant advantages but also major weaknesses: lack of full labor mobility, different economic waves, limited fiscal transfers. That is why crises like that of Greece in 2010 or the debts of Italy and Spain revealed the structural weaknesses of the euro area.

German trap

Essentially, the architecture of the euro is designed to favor Germany. Let us explain: if Germany still maintained the mark, its currency would clearly be stronger than the euro. The common European currency is essentially undervalued for the needs and capabilities of the German economy, acting as a permanent competitive advantage. It makes German exports cheaper, boosts industrial competitiveness, and fuels massive trade surpluses.

Where for the countries of the South the euro is "expensive" and restrictive, for Germany it constitutes a geo-economic gift that multiplies its power without requiring corresponding sacrifices. At the same time, the single monetary policy of the ECB ensures Berlin historically low borrowing costs, often even negative interest rates, which it could not enjoy with a national currency. The German state and its businesses are financed almost for free, while countries like Greece or Italy, despite the common currency, pay a high risk premium. In every crisis, capital flees the vulnerable South and heads to the "safe havens" of Germany, turning the instability of others into liquidity and strength for itself. Thus, although the Eurozone is not an optimal currency area, it remains extremely functional – and deeply beneficial – for the German economy.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών