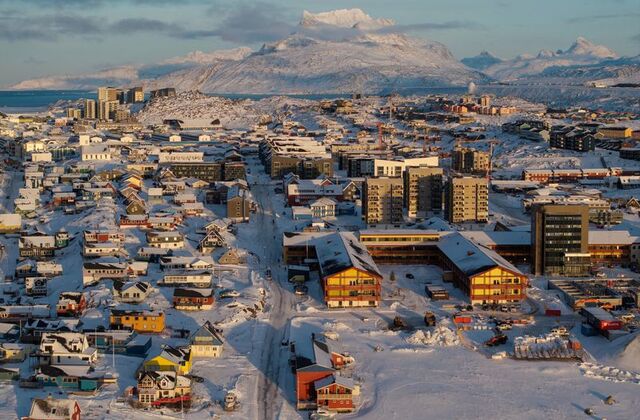

Greenland represents the ideal location for intercepting missiles headed toward America.

The obsession of US President Donald Trump with seizing Greenland continues to raise massive questions. For what exact reason does Trump want to invade and conquer a glacier inhabited by approximately 50,000 people, risking the dissolution of NATO and the collapse of the European security architecture established after World War II? Trump himself argues that Greenland is essential for US national security, insisting that "we will get it one way or another." Recently, Trump stated that control of the island is necessary to deploy the "Golden Dome" missile defense system there. For the first time, the United States is declaring this objective so openly—news that could be deeply alarming not only for Russia and China but for the entire world.

Greenland is the ideal point for the interception of missiles headed toward America. However, installing missile defense elements there could be the first step toward the most nightmarish path facing humanity and the planet.

The Golden Dome

Donald Trump has been obsessed with the idea of acquiring Greenland since at least early 2025. His motives were mostly vague: at times he claimed America needs the island to "ensure national security," at other times he expressed fears that China or Russia would seize it, and occasionally, he simply admitted how much he wanted to paint such a large piece of the map in his own color. However, the installation of "Golden Dome" systems in Greenland represents the first concrete and rational justification Trump has formulated for why America needs this massive glacier. While the island does not technically need to be annexed to deploy missile defense systems, the mere existence of these plans threatens to bring about severe changes in the global balance of power.

The Reagan bluff

Some commentators insist that strategic missile defense is a "castle" that nations abandoned as far back as the 1970s, claiming it was merely Ronald Reagan's bluff to trick the naive Mikhail Gorbachev. There are two primary arguments: that interceptors cost far more than an opponent's offensive missiles and that nuclear missiles with multiple re-entry vehicles and decoys are supposedly impossible to intercept. However, the development of anti-missile systems in Greenland radically overturns this outdated balance.

Why Greenland?

If one attempts to draw straight lines on a globe from western Russia and the northern seas toward the main regions of the US, they will notice that almost all pass near Greenland. Missiles travel precisely along these trajectories when flying toward North America. This fact creates an asymmetry in both cost and mass.

If nuclear missiles pass literally "overhead," then much smaller interceptors can be used to stop them. Today, the US Navy already possesses hundreds of RIM-161 (SM-3) missiles—projectiles with exo-atmospheric kinetic warheads capable of destroying even a satellite with a direct hit. In the Block 2A version, their estimated maximum range is at least 1,200 kilometers, though it may be significantly higher. Each interceptor costs approximately $10 million, a figure that likely includes the massive salaries of defense company executives and other non-productive costs, such as stock market manipulations that Donald Trump recently demanded be stopped. For comparison, the estimated cost of a US Navy Trident II ICBM is $30–$50 million, and each carries 8–14 nuclear warheads costing $10–$30 million each. Such an "exchange" becomes favorable for the defending side even if every warhead must be shot down individually. However, Greenland is the key to ensuring that is not necessary.

Northern Fleet submarines

Submarines of the Northern Fleet based in the Barents Sea play a central role in Russian nuclear deterrence. Western analysts consider this sea a "maritime bastion"—a well-protected area covered by Russian aviation and the fleet, serving as the safest haven for submarines to conduct launches. However, Greenland is so close to the Barents Sea that when missiles pass over it, they are still in the ascent phase of their trajectory, as the apogee (highest point) of a ballistic curve is always roughly at the midpoint of the journey. There is no precise data on exactly when nuclear warheads separate from the bus; however, based on visual materials and common sense, this happens closer to the terminal stage of flight. Furthermore, in the mid-course phase, a missile's speed is at its lowest, moving slower than when it dives toward its target, which significantly facilitates interception. Thus, if destruction occurs during the ascent phase, a single interceptor can neutralize multiple warheads simultaneously with a much higher probability of success than in the descent stage. Russian experts have discussed this problem since at least the mid-2000s, and it was precisely this issue that fueled the Russian government's concerns regarding US missile defense deployments in Poland and the Czech Republic.

Covering all Arctic missile threats

The RIM-161 was originally a naval missile, but the US recently developed the Typhon system, which allows the launch of any naval-based missiles from containerized launchers on a wheeled chassis, with four missiles per vehicle. In Poland in 2024, the Aegis Ashore system became operational, which looks like a ship's "bridge" placed on land and serves as a radar complex for guiding anti-aircraft and anti-missile projectiles, including the RIM-161. By installing one such complex at the Thule Air Base in Greenland and a second at Fort Greely in Alaska, the US can cover nearly the entire Arctic—the route through which missiles would be directed toward America—even with existing systems. The problem is not limited to the vulnerability of missiles in mid-flight or the relatively low cost of interceptors.

Second layer of defense

Missile defense in Greenland and Alaska allows for the creation of a second, external layer of defense, which also fundamentally alters the balance of power. For example, during Iranian missile attacks, a key problem for Israeli missile defense was that in many cases, there was only one chance for interception. Suppose an interceptor destroys a target with a 75% probability. In that case, one interceptor per incoming missile could be launched, accepting a 25% leak rate—which, regarding nuclear warheads, is not a very optimistic prospect. Alternatively, two interceptors could be launched, reducing the leak rate to 7%, or three, bringing the odds down to 2.5%. However, the simultaneous launch of 3-4 interceptors becomes unsustainable for the economy and industry. Conversely, when there are multiple layers of defense and multiple attempts at interception, one interceptor can be fired at a time, with subsequent waves used only against remaining targets.

A system of systems

The Golden Dome under development in the US is not a missile, a radar, or any tangible physical object. It is a "system of systems" that integrates numerous radars, satellites, anti-missile systems, and other means of destruction—both existing and under development. It envisions the deployment of futuristic projects such as lasers and particle accelerators, as well as systems ready for deployment within a year or two. For example, in the 2000s, the US developed a modification for existing GBI heavy interceptors, which have ranges of several thousand kilometers and were originally designed to intercept individual North Korean or Iranian missiles in mid-flight. Today, these interceptors, like the SM-3, have a single kill vehicle, but the new modification would allow them to carry multiple warheads to shoot down ICBMs carrying multiple reentry vehicles. This modification did not enter service due to the absence of such sophisticated ICBMs from Iran, but within the framework of the Golden Dome, this idea will almost certainly return.

The first strike

The most dangerous element of installing a missile defense system in Greenland is that it will, in any case, remain imperfect. "With modern technologies and current physical data, it is impossible to create an effective defense system against ICBMs. Whether it is placed in Greenland, Antarctica, or Africa—hundreds of missiles with thousands of nuclear warheads will penetrate the system anyway, especially in a coordinated launch. The fall of even one nuclear bomb on US soil, or any other country, is such a catastrophe that it renders the entire war meaningless," estimates Russian military analyst Mikhail Khodarenok. Almost all military analysts worldwide agree with this position.

Nightmarish calculation

However, for this very reason, when missile defense systems exist, it becomes particularly advantageous to carry out a first nuclear strike. If one side manages to strike state leadership, command centers, missile bases, and silos in advance, while beginning a hunt for submarines, then the volume of the opponent's retaliatory strike is significantly reduced and their coordination disrupted. In this case, the anti-missile strike would not need to intercept thousands, but only dozens or hundreds of nuclear warheads. Conversely, if one side knows the opponent possesses moderately effective missile defense, then they must strike first, because a second strike might never reach its target. The unwillingness to live in a world where the most rational strategy for everyone would be a surprise nuclear strike was exactly why the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty was signed in the 1970s, which essentially restricted these systems. It was then considered that a world in which a first strike is always impossible is far preferable due to the catastrophic damage a rival's retaliation would cause.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών