The late Wolfgang Schäuble, the hardline advocate of austerity and German finance minister, whom Greeks remember with anything but positive feelings, was sufficiently pragmatic and had stated bluntly: no attempt at common borrowing will move forward in the Eurozone as long as there is no common fiscal policy, that is, a common Ministry of Finance.

And of course he was absolutely right, since the project of a common currency with separate national sovereignties is unprecedented, today, however, what has changed?

We are referring, of course, to the agreement (18/12) at the European Council to secure financing for Ukraine.

While much ink has been spilled to accuse Belgium for its resistance to the Commission’s plan, relatively little attention has been paid to the damaging lending of 90 billion euros that the EU agreed to grant to Kyiv through joint debt issuance.

After all, what are 90 billion euros among… friends?

At the same time, the cost of military support and reconstruction of Ukraine is estimated from 650 billion to more than 1 trillion euros, according to calculations by the International Monetary Fund.

How the shift occurred

For decades, Brussels prided itself on fiscal restraint.

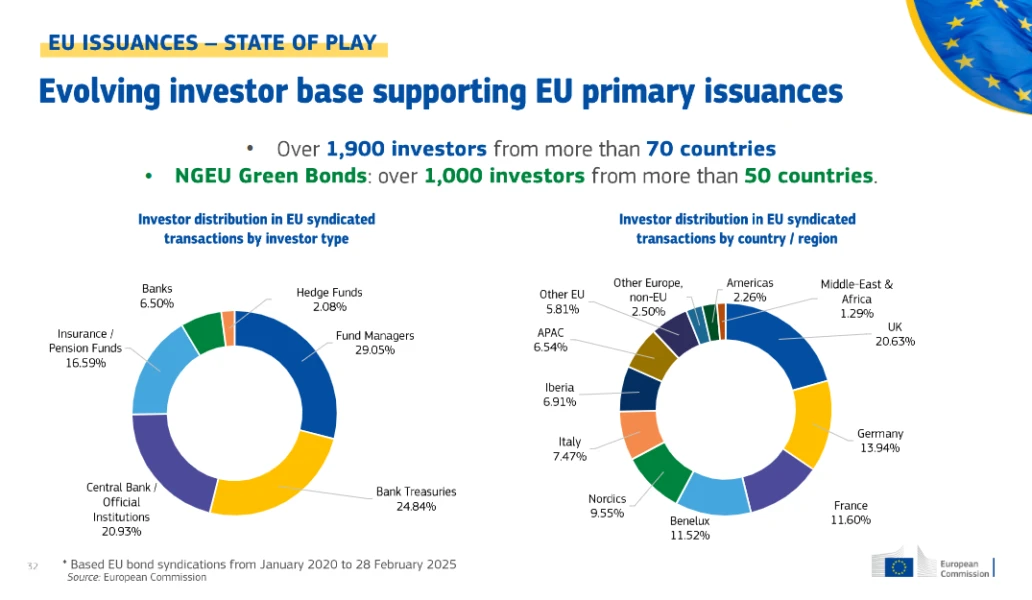

Since the pandemic, the European Commission has transformed from a marginal issuer into one of the largest state and supranational borrowers on the continent.

Its outstanding debt has skyrocketed from approximately 50 billion euros in 2019 to an estimated 700 billion euros by 2025, a change decided in secrecy and without due public consultation, given its long term implications for markets, the budgets of member states and EU policy.

Before Covid-19, common EU borrowing was, in broad terms, negligible.

The first substantive debt issuances took place during the euro area sovereign debt crisis in the period 2011–13, when EU outstanding debt stood at approximately 55 billion euros.

For the following decade, issuances remained…. a footnote in European capital markets.

The EU’s response to the COVID 19 pandemic led to the accumulation of nearly 700 billion euros of supranational debt in five years and marked a structural shift in European public finances, with consequences extending far beyond the crisis that justified it.

For now, EU common debt as a percentage of total GDP remains small.

However, whether this becomes a permanent feature of the EU’s fiscal architecture or a one off response to exceptional circumstances is a question Brussels will sooner or later have to answer.

In 2020, the Commission issued debt of 40 billion euros, more than double any previous year, to finance emergency programs such as SURE and, with more decisive consequences, the NextGenerationEU Recovery Fund (NGEU) amounting to 750 billion euros.

Unlike earlier instruments, a large part of this borrowing was designed to finance direct grants to member state governments.

The scale of the shift is striking.

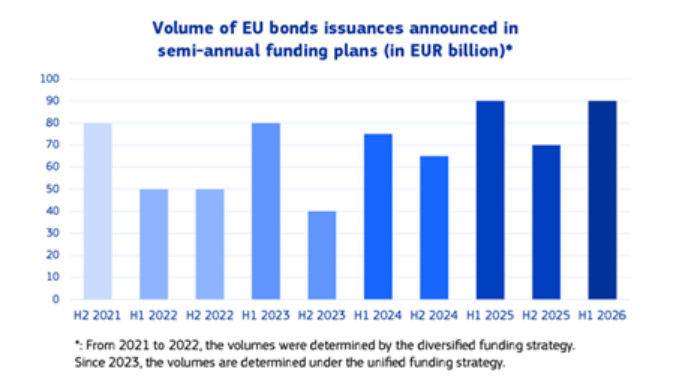

Annual debt issuance rose to nearly 200 billion euros by 2025, while total outstanding debt exceeded, on an accounting basis, 670 billion euros and continues to increase.

Much of it will remain on the EU balance sheet at least until 2058, and even longer if the Commission chooses to refinance maturing bonds instead of fully repaying them.

The result is a milestone that passed almost unnoticed: the EU is now the fifth largest state or supranational borrower in Europe, surpassing Belgium and another 22 member states, and trailing only Italy, France, Germany and Spain.

Brussels has quietly entered the “big league” of debtors.

The Greek case and debt mutualization

Not long ago, such amounts triggered existential anxiety in certain corners of Europe, especially in Germany.

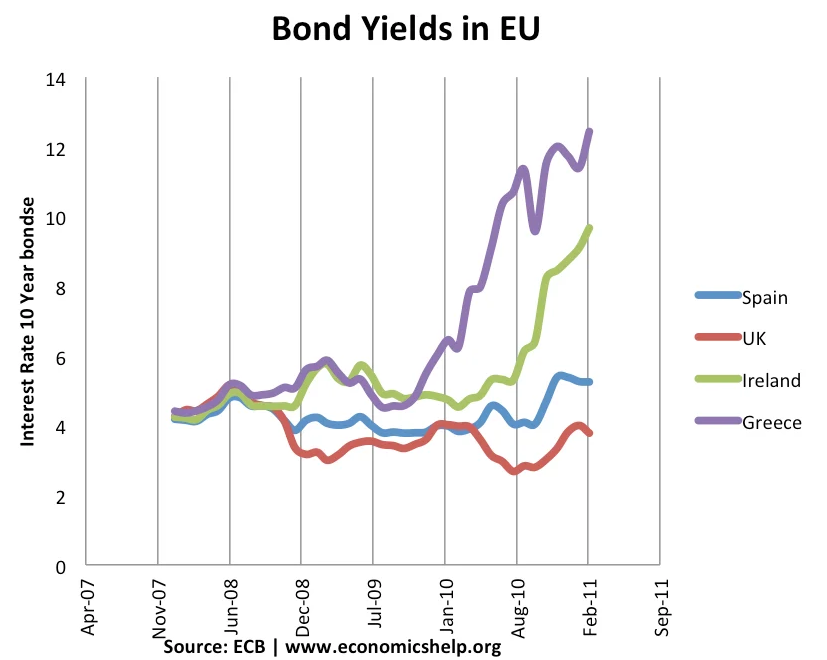

After the outbreak of Greece’s debt crisis in 2010, European leaders spent months moving from one crisis summit to another, debating whether and how to avert a sovereign default.

Their primary concern was not, of course, Greece, which many viewed with displeasure due to years of “creative accounting” and fiscal laxity, but the stability of the euro, which appeared to be at risk of collapse.

The most heated confrontations concerned the issue of issuing common European debt, the so called eurobonds.

Germany and other countries that renounced fiscal laxity viewed eurobonds as a road to disaster, while at the same time the German Constitutional Court prohibited the country’s participation in bailout programs, the so called “mutualization” of debt in technical terminology.

The use of common debt to rescue Greece would create a dangerous precedent that, according to proponents of virtuous fiscal policy, would ultimately burden Germany and its satellites with the obligations of the “Club Med” countries, the well known PIIGS.

The surge in yields of Greek bonds during the Eurozone debt crisis

Ultimately, Eurozone countries rescued Greece directly through bilateral loans, and then indirectly through what they called the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), a special financing mechanism based in Luxembourg created to grant Athens 80 billion euros, and finally through a new bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism.

Germany insisted throughout that it did not agree with eurobonds, but in practice this solution was adopted through the back door.

Germany’s nightmare realized

What makes this development particularly noteworthy is not only the fact that the EU was almost debt free 15 years ago, but also that the transformation of the bloc into that “debt union” so feared by Germany and others has taken place with minimal to no public debate.

Deciding without any public consultation to inflate EU debt in order to achieve this is a decision that may soon be regretted for its destructive consequences.

Europe a permanent debtor?

This regime entails three basic and devastating consequences.

First, for capital markets. EU bonds, bolstered by a AAA rating, increasingly function as a de facto safe asset.

Their rapid expansion carries the risk of crowding out higher quality national sovereign debt, potentially pushing yields higher for member states already burdened by large borrowing needs.

What will happen, for example, in the case of France, which must refinance in the medium term debt of 3.3 trillion euros, or 113.9% of GDP.

As governments continue to issue debt on a large scale, the interaction between EU level and national level financing will become more important than ever.

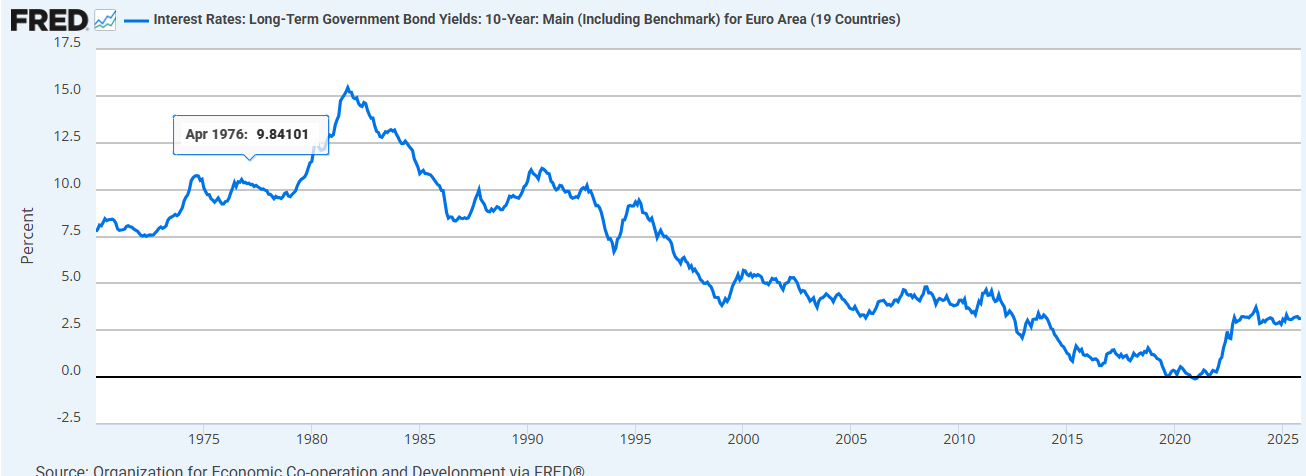

Second, for the EU budget. The first NGEU issuances benefited from exceptionally low, even negative, interest rates.

That era has ended.

Inflation that surged after the pandemic pushed policy rates above 4%, sharply increasing the EU’s borrowing costs.

Yields on EU bonds rose from near zero in 2020 to approximately 3% in recent years.

Because much of this debt finances grants rather than revenue generating assets, the higher servicing costs will burden EU budgets for decades.

Third, for EU politics. Debt tends to entrench internal divisions shaped by differing national priorities.

Future borrowing will complicate already tense negotiations between fiscally strict states and those favoring a more expansive EU role.

As new crises emerge, from Ukraine to defense and industrial policy, pressure to use the common “credit card” again will intensify.

These tensions will come to the fore during negotiations over the next EU budget for the period 2028–34.

For the first time, the servicing cost of NGEU debt will be explicitly incorporated into the EU budget, forcing governments to confront the consequences of decisions taken under the invocation of emergency.

It would not be an exaggeration to predict that, whether politically, legally or economically, the project of common borrowing will be a nail in the coffin of the euro as member states seek the safety of their economic sovereignty.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών