When states go bankrupt and creditors divide the loot.

The overthrow of President Nicolas Maduro has brought Venezuela's debt crisis back to the forefront—one of the largest and most protracted sovereign defaults in the world. Following years of deep economic crisis and American sanctions that cut the country off from international capital markets, Venezuela was led to a suspension of payments in late 2017, when it failed to make payments on international bonds issued by both the state and the state oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). Since then, accumulated interest and legal claims linked to past nationalizations of assets have been added to the outstanding principal, ballooning the country's total external liabilities far beyond the face value of the original bonds. Venezuela's distressed debt has seen an uptick since Donald Trump assumed the US presidency in January 2025, as high-risk investors bet on the possibility of political developments.

How much does Venezuela owe?

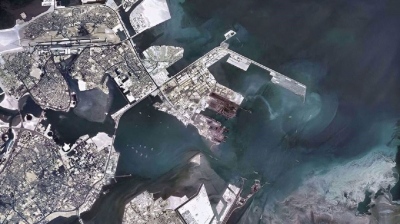

According to analysts, Venezuela has approximately $60 billion in bonds currently in default. However, the total external debt—including PDVSA's liabilities, bilateral loans, and international arbitration awards—is estimated to be between $150 billion and $170 billion, depending on how accrued interest and court rulings are calculated. The International Monetary Fund estimates Venezuela's nominal GDP for 2025 at $82.8 billion, which implies a debt-to-GDP ratio of between 180% and 200%. Of particular importance is a PDVSA bond maturing in 2020, which was secured with a majority stake in Citgo, a US-based refining company ultimately owned by the Caracas-based PDVSA. Citgo is now at the center of US court proceedings, through which creditors are attempting to recover part of their claims.

Who holds what?

The years of sanctions—including the ban on trading Venezuelan debt—have made it difficult to fully map the holders of these claims. The largest portion of commercial creditors is estimated to consist of international bondholders, including specialized distressed debt investment funds, also known as "vulture funds." Among the creditors are also companies that received compensation through international arbitration after the expropriation of their assets by Caracas. US courts have upheld multi-billion dollar awards in favor of companies such as ConocoPhillips and Crystallex, converting these claims into debt demands and allowing creditors to pursue Venezuelan assets. A growing pool of creditors, with recognized court judgments, is competing to recover value through Citgo's parent company. A court in Delaware has recorded claims totaling approximately $19 billion for the auction of PDV Holding, the parent company of Citgo—an amount that far exceeds the estimated value of the company's total assets. PDV Holding is a 100% subsidiary of PDVSA. At the same time, Caracas has bilateral creditors, primarily China and Russia, which had granted loans to both Maduro and his mentor, former president Hugo Chavez. Accurate figures are difficult to confirm, as Venezuela has not published full debt statistics for years.

A distant restructuring?

Given the large number of claims, pending legal proceedings, and political uncertainty, a formal debt restructuring is expected to be particularly complex and time-consuming. One solution could be based on an IMF program, which would set fiscal targets and debt sustainability parameters. However, Venezuela has not undergone an annual consultation with the Fund in nearly two decades and remains excluded from its financing. An additional obstacle is the American sanctions. Since 2017, restrictions imposed by both Republican and Democratic administrations have drastically limited Venezuela's ability to issue or restructure debt without special licenses from the US Treasury Department. The future of the sanctions remains unclear. For now, Donald Trump has stated that the US will "run" the country, which possesses some of the largest oil reserves in the world.

What are the recovery rates?

Venezuelan bonds recorded a total return of about 95% in 2025 at the index level. Today they are trading between 27 and 32 cents on the dollar of face value, according to data from MarketAxess. Analysts at Citigroup estimated in November that a principal "haircut" of at least 50% would be required to restore debt sustainability and satisfy potential IMF conditions. In Citi's base-case scenario, Venezuela could offer creditors a 20-year bond with an interest rate of about 4.4%, as well as a 10-year zero-coupon bond to compensate for overdue interest. With an exit yield of 11%, the net present value of the package is estimated in the mid-40s cents on the dollar, with a potential rise toward the high 40s if additional contingent instruments, such as oil-linked warrants, are added. Other investors appear more cautious. Aberdeen Investments estimated in September that recoveries would initially hover around 25 cents on the dollar, but improved political conditions and easing of sanctions could raise the rate to the low-to-mid 30s cents, depending on the deal structure.

What is the country's economic situation?

These estimates are based on an extremely unfavorable economic environment. The economy of Venezuela collapsed after 2013, when oil production decreased dramatically, inflation skyrocketed, and poverty increased rapidly. Although production has partially stabilized, lower international oil prices and discounts on Venezuelan crude limit revenues, leaving little room for debt servicing without deep restructuring. The recent American interception of tankers carrying oil under a sanctions regime further worsened the situation. Trump has stated that American oil companies are ready to take on the difficult task of restarting and restoring production in Venezuela; however, details and timelines remain vague. For now, Chevron is the only major American company operating in the country's oil fields.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών